By way of introduction – this is the Third Way. But first let us see what the other two ways look like.

THE FIRST WAY

I would be using this term to refer to the worldview and politics of the PFDJ as a political party currently in charge of guiding and administering government in Eritrea. The term does not refer to the Eritrean government in any form that implies the implementation function of policies or to any persons employed and assigned to bureaucratic functions. Government in this definition is policy-neutral in that it does what politicians tell it to do. In all that this term (First Way) is used, a government (including all military and civil functions) reflecting the true aspirations of the Eritrean people has since independence been serving the nation selflessly and fanatically in pursuit of the realization of “the Eritrean Dream” of heaven on Earth.

The “true aspirations of the Eritrean people” is a cross-section of “the Eritrean dream” at any point in time. Political parties or group of politicians, who end up assuming that function determine what aspects of the Eritrean dream take precedence at any given point in time. Government as a bureaucracy is not responsible for how politicians end up controlling political power and the seat of directing its functions at the level of legislation. Government can only assume (and very legitimately so) that any projects assigned to it by politicians in power at any point in time are a cross-section of the true aspirations of the people.

The “Eritrean Dream” itself must be taken as given and an absolute constant by all reasonable Eritreans who agree on the basic proposition that the Eritrean revolution (the armed struggle) was a true reflection of the aspirations of the Eritrean people. This simple fact, for all practical purposes, is in the truth that all Eritrean constitutions, political programs and all formal documents proposed by any Eritrean organization must share an identical conception of Eritrea as a dream. All departures from this constant conception are illegitimate. The parameters of these constant aspirations include (among others) things such as a sovereign nation, a united people, an independent state, and a strong government capable of maintaining all other parameters on a sustainable (uninterrupted) manner.

The basic function of any political party (group) is to answer one and only one question, which government needs to operationalize the proposed project of building and maintaining the nation: “Will success be measured by the extent to which society served the individual or the other way round?” Once politicians (in their purely philosophical personality) have answered this primary question, the rest is all a matter of technicalities and government bureaucrats (and politicians in bureaucratic personality) should be able to determine all tradeoffs necessary to mobilize the required resources. “Resources” includes human beings (when viewed as means to an end) and within this “allocation” function, bureaucrats should be able to determine, for example the level of human rights and individual liberties that the state given the projects and circumstances at hand may be able to afford.

The above is of course a simplification (by abstraction) of what politicians do at the functional level. Some may argue that, in practice, politicians do a lot more. In fact, the primary job of politicians is to hold government accountable. However, functions and institutions of accountability including the whole judiciary (and legal system) is practically redundant as we try to find out the subject matter of what might be understood as different alternatives. Since the goal of accountability as a function of governance is to ensure that bureaucrats do what politicians tell them to do, the role belongs to politicians in bureaucratic functions. Hence, all those involved in holding bureaucrats accountable may help improve systemic efficiencies and may in the long-run help us accumulate and store experiences thereby expanding the sphere of possibilities for politicians. Lawyers, human rights activists, and those who want to become ministers and generals to run state machinery do not contribute net value to our thinking about alternatives. Just like accountants, the only thing they can tell us is how to do what we had already decided to do in a better way.

In assessing where we stand in comparison to “the First Way”, we should view the PFDJ (ruling political party and source of current legislation) in relation to where it stands on the extent to which individuals should be subservient to society. Taking note of many experiences in history it is reasonable to assume, that the state does not start from having no say on the amount of liberty that individuals should surrender for the common good. It is the individuals, who usually start from a point, where they absolutely have no claim over any part of their personal liberty. The dialectical relationship between these two extremes usually takes the pattern whereby, hand in hand with the gradual achievement of the basic infrastructures of the state, more and more individual liberties tend to become redundant for the needs of state formation and maintenance. Even in situations where the state hardware is mature enough and no substantial components are in need of major expansion, the state does reserve the right to reclaim and confiscate individual liberties in circumstances of war and national emergencies (check with Edward Snowden for specifics).

THE SECOND WAY

I will use this term to refer to the Eritrean opposition as it stands today. The solid grounds that justify the emergence of an Eritrean opposition movement rest on the fact that the potential answer to the primary question (mentioned above) is by no means unique. There are no objective ways of determining the point, where we must allocate supremacy over individual liberties between the state and the individual. Where all citizens and groups are equally legitimate in the eyes of the people, one proven method of ensuring that the actual point selected is in fact the best possible choice, is through a democratic process of letting people vote on alternative points.

Here the ballot box would resolve the allocation (among competing politicians) of the right to pick the balance of individual liberties that government would take as given and use as the starter for the bureaucratic machine (for a given period). This is to say: beyond doubt the Eritrean opposition has a valid justification for its emergence. Given the circumstances of gross violations of basic rights and freedoms in Eritrea, the opposition has a very legitimate cause to fight for and opposition in our current situation is the must-do civic responsibility of every citizen. There is no question as to why we should oppose the situation of governance in Eritrea today and cooperate to search alternatives to make Eritrea better.

However, the right to compete is not absolute. It is a privilege that aspiring individuals and groups must earn by working hard to prove that they deserve to be trusted for having the nation’s interests at heart. The freedom of association (and all other positive political rights) should under no condition imply or be misunderstood as saying that states in the real world must let the free market determine their destiny. No sensible person can argue that the right to run people’s lives (that is what governments do) should be determined in the free market the same way that the prices of iPods are determined. Those who may be trusted to decide for the state, choices requiring the confiscation of more liberties by the state or the relinquishing of more liberties to individuals must enjoy considerable legitimacy among the people.

Someone is probably thinking of applying the same logic and concluding that the PFDJ does not enjoy any legitimacy simply because there are more people against it than for it. Eritrea as a “dream” that substantially departed from previous “dreams” came into existence in 1991 and had to start from somewhere, which happened to be the EPLF. The PFDJ did not come to power in 1991. You can only come to power if you are succeeding someone who was in power. The Eritrean government was set up on revolutionary legitimacy. Naturally, therefore, government started by confiscating all aspects of individual liberties. Similarly, any other organization may reinvent the wheel and acquire revolutionary legitimacy the same way that the PFDJ did.

That brings us to the defining feature of the “Second Way”, which is the exclusive focus on Regime Change in the hope of establishing political power through a Top-Down approach where the goods of political change would then trickle down to the masses. This core characteristic Regime-Change Agenda is the primary justification that lays the ground for alliances with any aliens as long as they share the goal of overthrowing the Eritrean government or weakening the state. The choice of establishing revolutionary legitimacy through alliance with the devil is in fact perfectly legitimate. It was done by the EPLF to drive the ELF out during the armed struggle.

However, such a strategy can only assume legitimacy where (before committing to an agreement) the Eritrean side of this devilish alliance must ensure that it is strong enough to impose its will and control the outcomes of the alliance. This was the case when the EPLF entered the devilish alliance with Weyane to defeat the ELF. It has never been the case with the Eritrean opposition and it is very unlikely that it will ever be the case. In the absence of this critical condition, any such alliance is either an irresponsible act or straight out treason punishable by law.

The Second Way, therefore, is an opposition movement that has a tiny minority organized into Ethiopia-affiliated groups and a silent majority very angry and confused helplessly sitting on the sidelines. This is how “Weyane Tigray” stole the genuine movement of good Eritreans – by mobilizing disgruntled Eritrean opportunists, vested interests, irresponsible power centers and a global conspiracy of regional intelligence organizations. The “Second Way”, therefore, represents Eritrean activists essentially fighting for an opposition movement that is controlled and is guaranteed to serve Ethiopian national security interests.

THE THIRD WAY

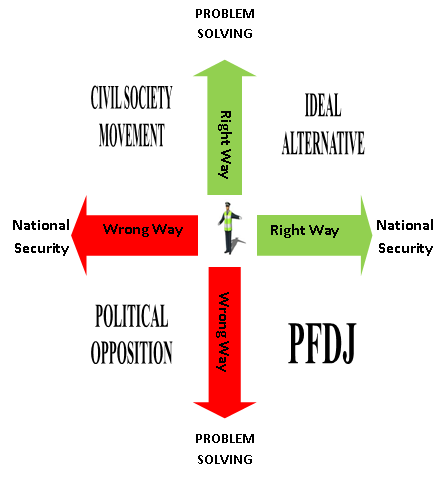

This is a proposal to respond to what I consider to be serious popular concerns with both sides of the equation: the Eritrean government’s misgivings on the one hand and the failings of the diaspora-based opposition on the other hand. It is a proposal to bring the opposition described in “the Second Way” above back to track. This proposal is unique in one critical argument and for now a very brief description of the idea is below in both its political and civil society components.

Political Activism

There have been three legitimate (in the sense that they share the Eritrean dream) versions of the “Second Way” opposition that promotes the Regime Change Agenda in a Zero-Sum game environment:

- Opposition (organized and spontaneous) that promotes various armed and peaceful means with the identical objective of effecting regime change in Eritrea. The difference between the armed and peaceful means of struggle in the traditional opposition movement is only a difference in the amount of violence that should be taken as necessary not in the character of the intended outcome of regime change.

- Opposition (primarily civil society groupings) that have at various times promoted the idea of negotiating with the PFDJ in order to come up with better government. The “Reform Movement” spearheaded by the G15 and G13 falls within this category. This brand represents the regime change agenda because it is the other side of the coin of overthrowing the government. While one side proposes confrontation, the other side seeks a negotiated exit for the PFDJ. This is explained by the fact that those who were (or claimed to be so) part of the Reform Movement did not have any problem merging with the diaspora opposition when they started to organize.

- Opposition (presumed to be active inside the Eritrean military) that promotes the idea of removing the regime through some kind of coup d’état or popular uprising that emulates the Arab Spring. The Forto rebellion and “Robocall activists” promoting similar Regime-Change uprisings are some examples.

I have excluded two legitimate categories of “Regime Change” opposition from consideration here because the proposal for the Third Way is limited to suggesting alternative ideas to entities that share the Eritrean dream as it stood on May 24th, 1991.

The first legitimate exception to the discussion above (and all subsequent discussions), which we must take very seriously is where any individual or organization does not agree on all the parameters (without exception) of the prevailing conception of “the Eritrean Dream”. If this is the case (as is true with the ethnic rights movement in our situation), neither the political party guiding government (PFDJ) nor the government implementing legislation has legitimate authority to negotiate accommodations.

Where the legitimacy of “the Eritrean Dream” is in question, revisions may come from two very legitimate sources: (a) debates that manage to persuade a critical mass of Eritreans to accept adjustments to the composition or structure of the parameters; (b) violent protests that succeed in enforcing de facto adjustments of parameters. The first was what we tried to do in the “land-grabber” debate and many debates before that – the second was what the Eritrean armed struggle did to Ethiopia, and what the armed factions of the ethnic rights movement is trying to do in Eritrea.

The second exception is the emerging movement of the New Unionists because unlike all other opposition variants, the Unionists are categorically against the existence of an Eritrean dream as independent from the Ethiopian dream. These are unquestionable enemies of the state of Eritrea and I am not wasting your time discussing their validity.

The common thread among all legitimate brands of the Second Way is the consensus on Regime Change and the subsequent vulnerability of forming alliances at random, with whoever shares the interest on conspiracy against Eritrea. All these brands have no interest in creating an alternative to the PFDJ as a political constituency. The concept of “alternative” must by definition rest on the assumption of coexistence. In the context of democratic (pluralist) thinking, “alternative” does not in any way imply or refer to something that will wipe out what already exists and sit on its place for good. For any two alternatives to exist, they must coexist in an environment and a formula where each would serve as the alternative to the other. Potentially the two must alternate in succession.

Wherever this is not the case, opposition necessarily becomes about regime change not about creating an alternative. Eritreans must be able to choose between what they already have and what promotes itself as alternative. Regime change relies on destroying this possibility of choice and is therefore by no means “opposition” in the standard conception of the word. It is illegal to advocate Regime Change in any country in the world including North Korea. Why should it be legal in Eritrea? It is illegal because it is a Trojan horse, which can carry very bad things.

The Third Way proposed here resolves the most critical question for what Eritreans should consider as legitimate opposition by removing the very credible possibility of collaboration with foreign enemies of the state. It holds the following four points to be true and beyond contention:

- Eritrea is a sovereign state and is entitled to treatment as a sovereign state

- The Eritrean government as the government of a sovereign state is the only Eritrean entity that is entitled to define the parameters of Eritrea’s national security interests

- No Eritrean activism may be considered legitimate unless it is carried out within the limits of the parameters of Eritrea’s national security interests (as defined by the Eritrean government)

- Since the Eritrean government has the duty to protect its citizens under emerging international practice, Eritreans maintain the right to debate and create alternative forms of governance within the parameters of Eritrean national security interests

This may sound idealistic and elitist. The first observation that jumps to mind is that the reason the opposition ended in this tight corner is because the PFDJ closed all doors and possibilities of creating alternatives. It is a dictatorship and it seeks to maintain power at all cost. That is definitely true and I am not one who needs proof of this fact. The bitter truth is that there is no other way for legitimate opposition to emerge.

It is true that every Eritrean should have the right to define what Eritrea’s national security interests are and therefore decide if specific actions violate these interests. The problem is that such a definition and hence the hypothetical right on which it is premised is illegal in all societies across the globe and throughout history. There is only one way to obtain the right to determine a country’s national security interests and that is by first assuming political power. There is no easy way and no shortcuts.

The Third Way opposition takes the exclusivist tendency of the PFDJ as given and seeks to create spaces of activism that do not violate the condition of legitimate opposition embedded in the four points above. It proposes four minimum conditions for characterizing rationality in any opposition activism:

- No opposition is legitimate unless it guarantees to promote better ways of defending Eritrea’s national security interests (as defined by the Eritrean government)

- No opposition is responsible if it seeks to reinvent the wheel by destroying what Eritreans have already achieved (even if it promises to rebuild from scratch)

- No opposition is rational if it seeks to create less choices for the Eritrean people or to recreate the single choice solution through a Regime Change Agenda

- No opposition is legal if it operates outside the prevailing laws of the state of Eritrea or attempts to obstruct their administration by the government of Eritrea, with the exception of situations that might arguably add value towards better governance

To say it bluntly – it is the responsibility of opposition activists to create their own spaces in the context of what is possible given the circumstances. We cannot blame a government described, by the opposition itself, as a dictatorship for not allowing spaces for the emergence of alternatives. It is not the destiny of the Eritrean people to be stomped in political games. Where the only way for an organized opposition movement to emerge is by adopting methods of struggle that place the very existence of the nation at risk, the Eritrean people are better off without such opposition.

The Third Way starts from the belief that there is actually much larger space of opposition within the limits of legitimate activism as defined above than within the highly vulnerable and legitimately questionable Regime change activism. It is a call to kick ourselves up and away from lazy & easy politics and compete of quality of governance not on quality of violence.

Human Rights Activism

The discussion in “the First Way” should lead to the conclusion that the state is the one that practices the charity of relinquishing individual liberties that are redundant for its functioning. “Redundancy” is the keyword. Withholding redundant individual liberties by the state is an extremely costly endeavor that no sensible government can afford. Under the assumption of governments as rational formations, no such government withholds redundant liberties. Where there is substantial unwarranted hoarding of restrictions to individual liberties by the state, there is room for very legitimate and effective activism promoting the expansion of individual liberties without threatening valid national security interests.

The perception that individuals may rise in rebellion and snatch individual liberties that the state had appropriated on objective legitimate grounds that prove their critical importance for its formation and maintenance is a total myth. Where such a rebellion of individuals does succeed in forcing the state to relinquish liberties that are critical (not redundant) for its maintenance, the state must necessarily collapse. Some of the phenomena of failed states, the most notable being Iraq, Libya and Syria are classic examples. In these cases, as in many other examples, groups of individuals acting as part of global conspiracies have succeeded in bringing the state to its knees by mobilizing supporters around well-documented proofs of state appropriation of individual liberties (without saying why the liberties were appropriated in the first place).

The constants of any legitimate Eritrean civil society and human rights activism must build on the following key considerations:

- The state of nature (for our purpose) is an anarchic order resting on the libertarian principle of Non-Aggression. Here individuals are essentially sovereign entities entitled to a full ownership and control over everything that affects their lives and choices. No individual or collective might violate this sovereign personal space except in the case of voluntary contractual agreement with the individual in question. The state is such a hypothetical contractual formation premised on the assumption, that the collective must violate some rights if it is to respect most other rights. The very minimum of the rights, which may not be violated by the state (i.e. what is left of the principle of Non-Aggression) is represented in the conception of Constitution (either codified or non-codified – both perfectly legitimate). Laws, legislations and policies enacted by government specify the contents of the basket of rights that are up for grabs (by activists) at any particular point in time and depending on circumstances. The “up for grabs” concept is the same one presented above as “redundant”.

- This is the point that every activist must memorize: FOR ANY ASPECT OF YOUR LIFE TO BE A RIGHT, IT MUST FIRST BE LEGAL. While every American has the right to become President, it is illegal to become a US President if you are not born in the USA. Therefore, it is not a right as long as that law is in place. Free movement of people is a human right. Free movement to Lampedusa without a proper visa is illegal and therefore not a human right as long as Italian xenophobic laws are in place.

- Human Rights violations are those concerns that arise from the state not respecting its own laws and obligations under international law. They are not concerns that arise because of those laws that sovereign states are entitled to enact and enforce. If compulsory national service is the law in Eritrea, even if it ends up destroying every life in the country, evasion of national service or attempts to obstruct its implementation is illegal as long as that law is in place.

Under the circumstances, evasion of or escaping from national service is not a human right in Eritrea and on the contrary, it is a felony. Similarly, if Eritrea has a law that requires of Eritreans in the diaspora to pay a 2% tax, it is a felony to evade, encourage people to break the law or obstruct under any justification the smooth administration of the law as long as it is in place. Since Eritrea has a law that requires all citizens sent on official duty to return upon completion of assignment, what I did by not returning, whatever the justification, was felony not an exercise of my human right in an absolute sense. The deadlock in the transnational space of refugee advocacy arises precisely from that fact that while the identical act is (legitimately) a felony in one country it is an internationally protected human right in others.

- Fortunately, governments do not have a free hand on their citizens – not anymore. There was a time when Nazi Germany could enact laws to exterminate whole populations on primordial specifications. There was a time when Stalin’s communists could declare a socio-economic class unworthy of survival. There was a time when a section of the Rwandan population could just pick machetes and hack the other section out of the map. Things have changed since then and the international community may hold governments accountable for the safety and well-being of their citizens under “the Responsibility (of the international community) to Protect”.

All these atrocities arise because of explicit and implicit laws and policies i.e. the implied concerns happen because of those laws not in spite of them. Since the remedy is to replace those laws and the regimes that practice them (if necessary), they fall within the exclusive domain of politicians and political activism and have very little to do with civil society and human rights activism. The exclusive domain of the latter (human rights activism) is where violations and atrocities take place in spite of the restrictions that prevail in the laws and policies enacted and enforced by the states in question.

Restricting Eritrean human rights activism within this specific domain has three critical advantages:

- It steals the human rights agenda from the controversial domain of politics in our highly polarized situation. Since the goal of such activism is to hold the Eritrean government accountable for the spirit and letter of its own laws, proclamations and policies, there is no room for supporters of the PFDJ to excuse themselves from valid concerns by all sensible Eritreans.

- It adds net value towards the government’s efforts to build a strong and better state of Eritrea as it brings to the attention of the public discrepancies that arise at the implementation stage of public policy. It makes government more efficient and eliminates waste due to uncontrolled human factors of enforcement including the corruption of public offices.

- It has the capacity to reach a much larger constituency of law-abiding Eritreans, who in spite of their obedient service to the nation are caught up under potentially corrupt situations where government intervention is required. It expands the focus from a tiny minority of those to whom the laws that we are trying to improve do not apply anymore because they have already made it out of the country, to those for whom change would make a difference.

- It makes the opposition camp competitive, because unlike the easy task of following refugee boats in the Mediterranean and human traffickers in the Sinai, this paradigm calls in the whole spectrum of the crisis of governance into the opposition agenda.

- It is also critical in holding the Eritrean government and its embassies abroad accountable for the advocacy and protection of all Eritrean citizens abroad. In the context of civil society and human rights activism that hold the Eritrean government accountable to its own laws and proclamations, Eritrean embassies protected by the opposition’s Zero-Sum game cannot enjoy the easy pass of neglecting or collaborating to trash the concerns of refugees and human traffickers. There is much to be gained by calling in well funded Eritrean diplomats into the protection of our diaspora: they get more money and we get better services.

So my friend, stop arguing and head to the closest consulate and ask the “Hisabey kidney iyu?” They should be able to tell you.